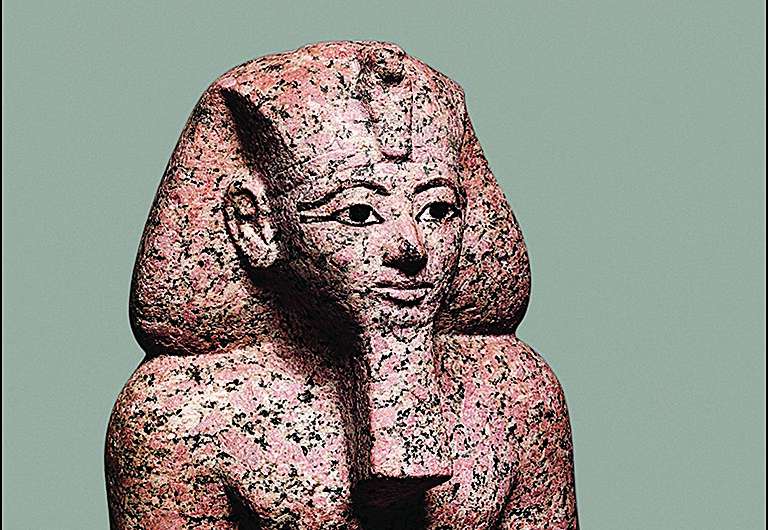

Unearthing the past can be a journey filled with surprises, and in the case of Queen Hatshepsut, it’s especially heartwarming. New insights into the fate of her statues challenge long-held beliefs, suggesting a more respectful treatment of this remarkable female pharaoh than previously thought.

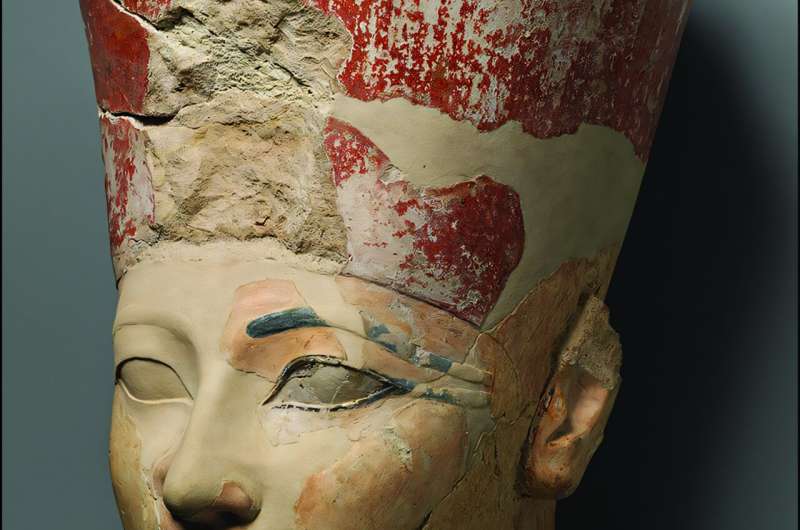

Queen Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most celebrated rulers and one of the few female pharaohs, left an indelible mark on history. Yet, after her death, her legacy faced a turbulent storm of political strife. Excavations in the 1920s at Deir el-Bahri, where her beautiful temple stands, brought to light a scattering of her statues, many shattered and fragmented.

For decades, it was widely believed that these damages stemmed from the actions of her successor, Thutmose III, who sought to erase her memory. However, new research led by Jun Yi Wong from the University of Toronto opens a door to a different interpretation. According to Wong, many of Hatshepsut’s statues actually remained in good condition, hinting that the narrative of revenge might be more complex than previously thought.

Wong meticulously sifted through field notes, photographs, and correspondence from the original excavations and made some fascinating discoveries. It turns out, many of the statues sustained damages not linked to Thutmose III’s animosity but rather due to their later reuse as construction materials. Over time, these ancient artifacts were repurposed for practical use, leading to their physical deterioration.

Moreover, the specific way the statues were damaged—broken at their joints—follows a ritualistic pattern recognizable in ancient Egyptian practices known as “deactivation.” This method was employed historically to neutralize the perceived power of statues, and it was not exclusive to Hatshepsut; other pharaohs underwent similar treatment.

“This doesn’t necessarily imply hostility,” explains Wong. “Instead, it signifies a complex ritual rather than simple vindictiveness.” The analysis reveals that the actions taken regarding Hatshepsut’s statues may have been shaped more by ritual needs than by personal vendettas, providing a more compassionate lens through which to view her legacy.

The narrative around Hatshepsut is undeniably intricate; while there were elements of persecution against her, this fresh understanding uncovers layers that deserve acknowledgment. It seems that in her death, she was afforded a treatment akin to those who ruled before her.

In conclusion, while Thutmose III’s motivations remain entwined with political machinations, Wong’s work invites us to consider the possibility of a more respectful ritualistic intention behind the actions taken towards Hatshepsut’s statues. It’s a beautiful, nuanced addition to the story of a remarkable woman who paved the way for future generations.

More information:

The afterlife of Hatshepsut’s statuary, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.64

If you would like to see similar science posts like this, click here & share this article with your friends!